Stonks and girl math: clearing the confusion around financial literacy

Get in loser, we're going to become financially literate

We all remember seeing those ads on TV for the Reading and Writing hotline, to improve literacy rates, but soon there may be a need for a Financial Literacy hotline.

According to NAB research, younger Australians are reporting continuously declining financial literacy levels, alongside a greater risk of financial hardship.

Financial literacy is the ability to understand and apply financial concepts. These concepts include budgeting, financial management and investing.

To be financially literate, one does not need to be Warren Buffet or a nepo-baby with a $25 million trust fund. They simply need to know how to work with their money and manage it correctly.

NAB’s Financial Hardship survey showed that men aged 50-64 (82 per cent) and women over 65 years old (81 per cent) had the highest self-reported financial literacy. The largest gap in financial understanding was amongst women aged 18-29, with 3 in 10 (31 per cent) rating their financial literacy ‘fair’ or ‘poor’, significantly higher than any other group.

NAB’s former Head of Customer Vulnerability, Michael Chambers, said many people are one unexpected life event away from financial hardship.

“1 in 4 Australians say they don’t have enough money for an emergency. With rising interest rates and increased cost of living, people’s financial literacy and understanding of their financial situation is being tested,” Chambers said.

“Financial literacy is about more than being able to put together a budget, it extends to things like understanding savings, borrowing and planning so you can meet your goals.

“Research shows that people being over-confident in their financial understanding can be just as problematic as not having basic knowledge in the first place.”

That over- or under-confidence can contribute to the misrepresentation of financial literacy rates.

But how is that tested?

If I say, “The Big Three”, what do you think of?

The three major Australian commercial television networks – Seven, Nine and Ten?

Or perhaps the three major record labels – Universal, Sony and Warner?

Maybe you think of the three great allied powers during the Second World War – Great Britain, the United States and the Soviet Union?

I certainly doubt that you think of the Big Three financial literacy questions, a series of questions to determine a person’s financial knowledge.

Dr Annamaria Lusardi, founder and academic director of the Global Financial Literacy Excellence Centre and Dr Olivia S. Mitchell, professor at The Wharton School devised “The Big Three” financial literacy questions. These questions tackle three universal concepts in finance: testing knowledge on 1) compounding interest, 2) inflation and 3) risk diversification.

The multiple-choice questions don’t test knowledge of formulas or the ability to do a calculation.

They simply give respondents ballpark ranges to give their answers.

In addition, they give the option to say, “don’t know” or “refuse to answer”.

Want to put yourself to the test? Watch this video and see whether you’re financially literate or not!

How did you go? Let us know below…

Dr Lusardi said in a 2023 interview that the questions do not test “whether someone can price bonds”.

“We are not testing whether people are sophisticated investors.

“We are testing ‘do you know the ABCs of the basic concepts’, which we believe are really important for making financial decisions,” she said.

Dr Lusardi told the United States Senate Subcommittee on Children and Families in 2013 that “the vast majority of Americans do not have the financial knowledge they need.”

“This reality has implications for their lives and for the economic health of the country.

“Financial illiteracy is not only widespread, but it is particularly severe among specific groups of the population, including people aged 18 to 25.

“These youths just out of school and young adults beginning their careers are less financially knowledgeable than the general population,” she said.

While Dr Lusardi paints a pretty bleak picture in her testimony, back home, it’s not much better.

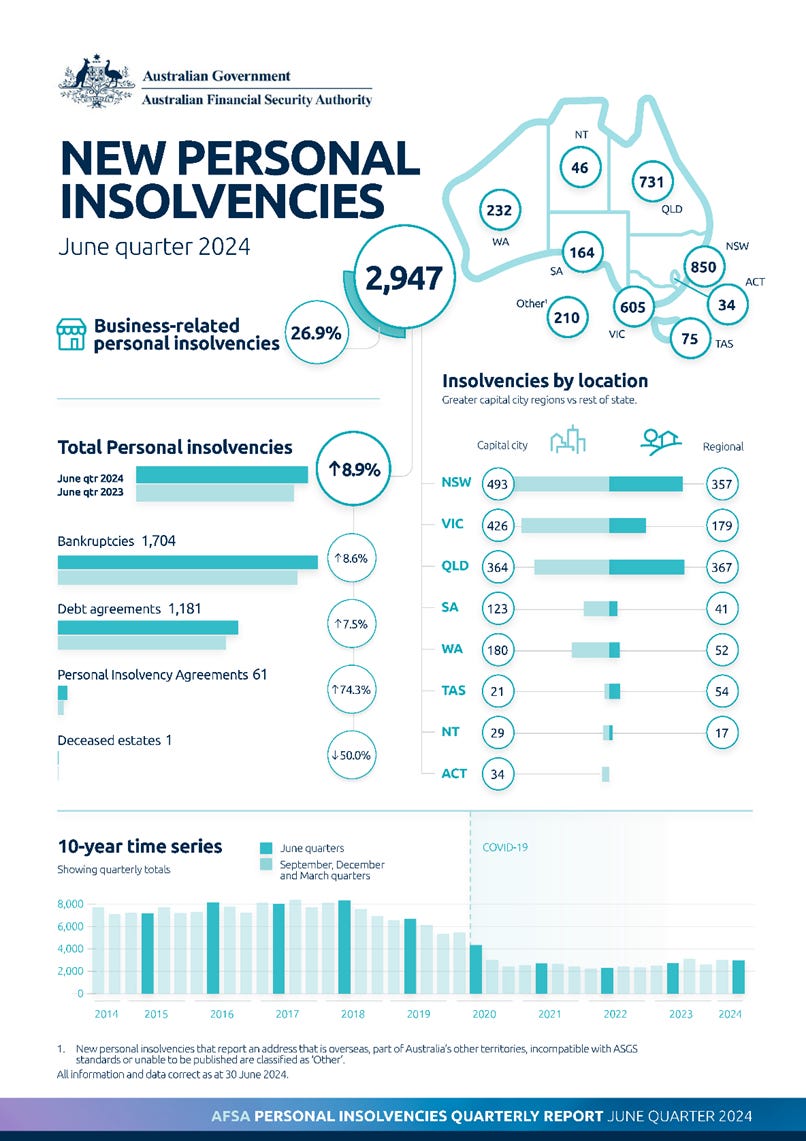

The impact of low financial literacy rates is clear, from the Australian Financial Security Authority’s (AFSA) quarterly personal insolvency statistics.

Personal insolvency is complicated finance talk for bankruptcy – when you cannot afford to pay your debts.

The June 2024 quarter report shows there were 2,947 new personal insolvencies in the 3-month period up to June 2024.

That’s an increase of 8.9 per cent, compared to the June quarter of 2023.

Without proper financial literacy, we could see this number increase each quarter.

This is not a new issue.

A 2005 research paper from the Queensland Parliament warned that without proper education, more and more bankruptcies will occur.

The research paper could very well have been made with a crystal ball, as it hit the nail on the head for a few statistics.

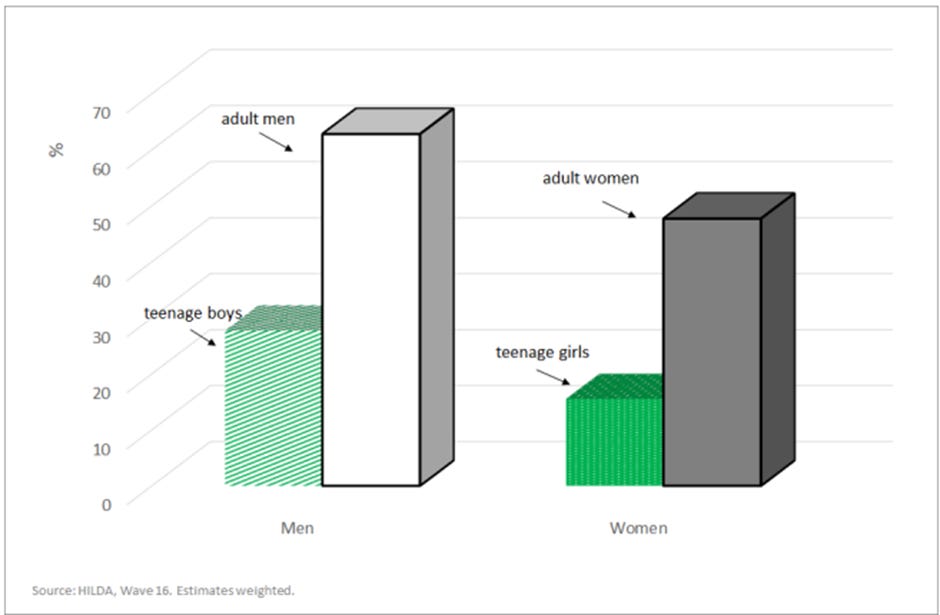

In 2020, a report from the University of Western Australia analysed results from the 2016 Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey.

It tested financial literacy using five questions, based on questions initially developed in The Big Three.

Based on responses, HILDA estimates that just over half of all adult Australians are financially literate.

Only 55 per cent.

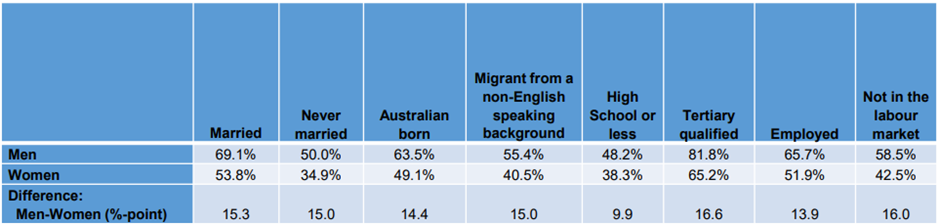

Significant gaps are clear between those born in Australia and immigrants, what level of education you have, and whether you are employed or not.

However, the most prevalent gap is gender, something the 2005 research paper attempted to avoid, by launching pilot financial planning workshops for women, clearly to minimal success.

63 per cent of Australian men are financially literate, compares to 48 per cent of Australian women.

“The gender gap is highly significant in a statistical sense,” it said in the report.

Can we pinpoint this gender gap, particularly in young people to a social media trend?

To be financially literate you do, however, need to not subscribe to the tenets of “Girl math”, a tongue-in-cheek TikTok trend that helps young people justify purchases.

While not a new way of thinking, the term was popularised by New Zealand radio show Fletch, Vaughan & Hayley.

Listeners call in, telling the hosts about their impulse purchase, asking for ways to justify it.

It goes like this…

Paid in cash? That’s free.

Paid $600 for concert tickets 6 months ago? Now it’s free.

A $300 jacket? Using girl math, that’s under $1 per day for a year. Basically free.

It’s a potentially harmful trend, and one that economists say is actually misleading.

Jacqui Dwyer, head of Information Department at the Reserve Bank of Australia said despite high achieving results from women in maths, there’s been a drop in enrolments for economics courses.

“The falling share of female students enrolled in economics is one of the most striking aspects of the decline in diversity in the discipline,” she said.

“It will also affect the composition of the economics profession for years to come. And yet women in economics have some distinctly different perspectives to their male counterparts from which the discipline and public policy can benefit.”

In 2022, Victorian girls did better than boys in most school subjects, except for maths and chemistry.

A similar pattern is found in New South Wales too.

So, where are girls falling behind?

Dr Laura De Zwaan is a Senior Lecturer at the QUT School of Accountancy. She has a research focus on financial literacy, specifically looking into ways that education can be improved.

She highlighted that between 14-year-olds, there isn’t much of a gender gap, but when talking to first year university students, there is.

“It’s because of the questions and the way we’re measuring it,” she said.

Dr De Zwaan’s research suggests that “The Big Three” are not equitable, finding that women are more likely to admit they don’t know, or refuse to answer, compared to men, who would take a guess.

“I think they’re really flawed in that regard, and what they’re measuring is confidence… What we say is that females are less confident than men and are more likely to not select an answer.

“When we were doing the research in the high schools, I would get the kids to tell me what they were thinking when looking at these questions, so it was really interesting to see them say ‘I don’t know the answer’.

“But [the questions] lack the context needed.

“When it’s just multiple choice, it means it is difficult for some people to answer, they doubt themselves.”

21-year-old Zac Englert says he “knows nothing” about money.

When tested, he scored 2/3 on the big three financial literacy questions.

He did not know what a stock mutual fund was, so he said “Don’t know” for question three.

He says that “money is such a taboo subject to talk about,”, likening it to US Department of Defence Directive 1304.26.

“It’s very don’t ask, don’t tell vibes to me,” he said.

For the unaware, "Don't ask, don't tell" was the official United States policy on military service of non-heterosexual people, brought in during the Clinton administration in 1993.

“I was always brought up on, you don't ask your parents how much they make, you don't ask people how much they make, you don't discuss wages, you just survive. It's one of those things that it feels wrong to bring up,” he said.

Still living at home, the 21-year-old says he only started talking to his parents after taking out a loan for a car.

“When I got the loan for [my first car], that was the first time I asked Mum about interest rates and all that sort of stuff, because that was never really taught to us in school,” he said.

He admits the conversation was a “very brief and broad explanation of the topic”, and only came out of a necessity.

“If I didn't need to get the loan for the car, it wouldn't have happened,” he said.

Dr De Zwaan said through all her research, she was surprised to learn that kids know more than we think.

“They struggle with the questions, but when we talked to them and asked about their home life, and talked about what happens when a bill arrives, they did know it.

“So, putting it in that context is really important,” she said.

Dr De Zwaan says young people do care about financial literacy; they just don’t have the knowledge.

“They’re a little bit scared, especially when we teach it through Maths, that’s not everybody’s strong suit, so it can deter them,” she said.

According to Dr De Zwaan’s research, a Maths class is not the optimal mode to teach students about financial literacy, emphasising that calculations are not the way to teach or test financial skills.

“It’s best done through stories.

“When we add that context, you’re much more likely to understand it, it has more impact than teaching through a formula,” she said.

“This project was a little while ago, so we hadn’t had a lot of inflation in Australia for a while, so kids really didn’t know anything about it, but one kid did!

“They said they had been watching YouTube videos about the history of Rome, and so he knew all about it from that… I think that shows, when we focus on these calculations, and have the kids pull out a calculator and know the formulas, they’re kind of disengaged, so learning through these stories is how we promote that engagement.”

“Putting it in different subjects gives us that context.

“In History, you could look at the financials of different historical societies,” she said.

When talking with Zac, it’s clear that stories are the way to improve financial literacy.

When asked about seeing his parents deal with financial matters, he remembers his father’s plumbing company going out of business.

“I remember getting lots of toys, and getting what I wanted, when I wanted it, and then I remember not getting toys… and I think as well, there was only two of us [kids at that time].

“If we saw [a toy] and it was cool, we'd be like, ‘oh, like, do you think we can get this?’ And he'd be like, yeah, sure,” he said.

Zac recalls that the company went out of business not long before his youngest sister was born.

“So, there's that, on top of that they've been given a financial burden of another child on the way, whilst also having their financial security sort of somewhat taken away from them.” he said.

It’s clear that financial illiteracy is sticking with people after they leave school, following them into their careers.

Dr De Zwaan says a lot of teachers aren’t confident with their own finances, making them less confident to teach these skills.

“Those teachers that aren’t as literate, they’ve gone through that same school system, so they’ve had those issues with the lack of financial education,” she said.

“There’s a lot of discussion that, really, it should be up to the families [to teach financial literacy].

“If we actually want to teach people, we should be exposing everyone to these concepts in real scenarios, because they’re so necessary in later life.”

Even if we started teaching financial concepts in schools tomorrow, according to Dr De Zwaan, it will take a while to see the effects.

“It can take a generation.

“You look at the time where financial literacy wasn’t a priority in schools, and it was only when those students going through became teachers, with low confidence and low literacy, did we have that change of ‘Oh, we’re going to put literacy back in’,” she said.

“The difference today is there is an enormous amount of resources out there.

“You have the Moneysmart website, which is full of information, easy to use… there’s the influencers too, some of them are absolute rubbish, but there are some who are really knowledgeable and give that knowledge back to the communities.”

Another interesting gap, presented in the HILDA research is that between married and unmarried women, there is an 18.9 per cent difference in their literacy.

Dr De Zwaan says the disparity between unmarried women and married women could be because of outdated household stereotypes being adhered to.

“For a lot of Australians, they’re quite progressive and they share the load, but for a lot of Australians it isn’t like that, and they still feel strongly towards those [traditional] roles… because of religious beliefs, or cultural views,” she said.

In researching this story, a total of 10 18–24-year-olds were assessed using The Big Three.

Only 3 of them can be considered financially literate.

Many refused to answer, out of fear, they said.

It is clear that amongst young people, money is a scary topic.

It’s not something they want to discuss or delve into.

It is clear that the education system needs to change and needs to change now.

If not, then we will continue through this cycle:

Student goes to school, doesn’t learn anything about finance, goes to university, becomes a somewhat productive member of society, has financial crises (be that bankruptcy, excessive debt, etc.), and passes this illiteracy onto the next generation.

So, you, gentle reader, must be wondering, what are the takeaways here, what can I do?

If you are a parent – pass on your knowledge and do it through stories, giving the proper context.

Gone are the days where the parents hid all discussions of finances from children.

If you are a young person sitting there wondering why you didn’t get any of the Big Three questions right, do something about that!

There are thousands of resources out there for you to self-educate yourself on financial matters.

Please note none of this is financial advice and does not take into account your personal circumstances. Seek professional advice.

If you are in trouble, financial counsellors and registered insolvency professionals can help to review individual situations and help plan an appropriate response.

Free confidential assistance is available through the National Debt Helpline or via phone at 1800 007 007.

For help with budgeting, Money Smart has some easy-to-use tools available at www.moneysmart.gov.au.

If this story has raised serious personal concerns, Lifeline is available 24/7 on 13 11 14.

This story was produced for my Journalism capstone unit at university.